There are beautiful towns and villages to visit all around the United Kingdom, with incredible activities for couples and families. But there isn’t many which can claim to be a plague village, so we felt it was a spot we had to explore. We drove to the little village of Eyam, a parish in the Derbyshire Dales, which is within the Peak District National Park. Our aim was to discover what made it so special and how they came to be known as the Eyam Plague Village.

There are beautiful towns and villages to visit all around the United Kingdom, with incredible activities for couples and families. But there isn’t many which can claim to be a plague village, so we felt it was a spot we had to explore. We drove to the little village of Eyam, a parish in the Derbyshire Dales, which is within the Peak District National Park. Our aim was to discover what made it so special and how they came to be known as the Eyam Plague Village.

Ad Disclaimer!

This website uses paid adverts and affiliate links, these come at no additional cost to you and help us to fund the operation of the website, meaning we can continue to provide you with valuable content.

The money received from these links and adverts do not influence any recommondations made within our content.

Page Contents

The History of Eyam Plague Village

The area has a raft of history, with evidence of habitation during the Roman era. Anglo-Saxon crosses which can be found in the cemetery, plus Norman and Middle Age additions to the village church (which dates back to the 14th century). But it is the 1665 plague outbreak which makes this small spot so famous and a popular area for tourists to visit.

In 1665 a bundle of cloth arrived from London for Alexander Hadfield who was the local tailor in Eyam, sadly it was flea infested. Noticing the bundle was damp, the tailor’s assistant George Viccars opened it up to warm by the fire. This gave the fleas the opportunity to infect George and he soon died, as did the others in the household.

Most people are aware of how the bubonic plague affected London, but little is told of how it spread throughout the country. But what really makes Eyam stand out is the response by the villagers as the disease took hold and passed from house to house. The rector at the time who was Reverend William Mompesson saw the speed in which the plague spread between the families. Unfortunately, not everyone in the village agreed with his beliefs and as such he turned to the ejected Puritan minister Thomas Stanley for support.

Both men were able to convince the villagers to introduce a number of precautions to slow the spread of the illness from May 1666. This included the relocation of church services to the more natural amphitheatre location of Cucklet Delph, so that it was in the open air and would reduce the risk of spreading the disease. That family members bury their own dead, which led to some villagers burying multiple family members including husbands, wives, and children. There are many burial spots which can still be found all over Eyam, some are close to the houses where the deceased lived. Finally, and most importantly they made the decision to quarantine the entire village and not allow anyone in or out, to prevent the spread to neighbouring villages and towns such as Sheffield.

To ensure the people of Eyam had enough supplies, the surrounding villages sent food and medicine which they would leave on marked rocks; one of them being the boundary stone. They made holes in the rocks and filled them with vinegar to disinfect the money that they left as payment.

To ensure the people of Eyam had enough supplies, the surrounding villages sent food and medicine which they would leave on marked rocks; one of them being the boundary stone. They made holes in the rocks and filled them with vinegar to disinfect the money that they left as payment.

During the 14 months that the plague ravaged Eyam it is believed to have killed 260 of the villagers, with only 83 surviving of the original 343 people (although these numbers have been challenged). Whether you lived or died appears to be random, as many who survived had been in close contact with someone who succumbed to the disease. An example of this is Elizabeth Hancock who stayed uninfected, despite burying her husband and six children in a mere eight days. Those graves are known as Riley graves and can still be found on the farm where they lived. Then you have the unofficial gravedigger Marshall Howe who despite handling many of the infected bodies, survived the plague.

What makes the history of this little village so important is the fact that between the first death and the last, the villagers made an extraordinary sacrifice by sealing off Eyam from the surrounding areas, so the plague didn’t spread.

Visting the Village of Eyam

By visiting this beautiful part of the Peak District, you’ll have the opportunity to wander around a quaint country style village. As you do you will learn about the incredible history of the plague and its effects on the villagers. It is more poignant because you will not only be able to visit a museum about the plague, but you can walk in the footsteps of those who were affected and see their homes which still stand today. The people in Eyam have taken great pride in maintaining their history and as such you can visit important places relating to this moment in time.

What really stood out to us as regular attraction visitors is the fact that Eyam is incredibly cheap, compared to many other places you may visit. Aside from the museum which we found to be a decent price for entry, the other locations you will see are free. We know how those costs can really rack up for families who simply want to head out for the day and discover something new. So, this is a great option and although the story is a little gruesome, they have made it interesting for kids.

Arriving and Parking

Because of how isolated Eyam is, you will find that the drive into the village is via lots of windy roads and cute villages. The best address for your sat nav is the car park address which is opposite the museum.

Because of how isolated Eyam is, you will find that the drive into the village is via lots of windy roads and cute villages. The best address for your sat nav is the car park address which is opposite the museum.

Hawkhill Road

Derbyshire

Eyam

S32 5QP

Depending on where you are coming from, here are the best routes to take.

- From the M1 – Take the Chesterfield exit and then follow signs for Bakewell. In Baslow (past the Chatsworth estate gates), take the right turn at the second large roundabout, past the church, and follow the road to the crossroads at Calver. Travel straight ahead, through Stoney Middleton, and then look out for signs to Eyam on the right. As you come into the village, take the first left turn and head past the church to find the car park.

- From Sheffield – Take the Hathersage and Castelton road out of the city and over the moor. At the Fox House inn, take care as the road makes a sharp right turn, then immediately after the pub, turn left down to Grindleford. At the bottom of the hill, cross the bridge, and follow the road through the village until you reach the crossroads at Calver. Turn right here, through Stoney Middleton, and then look out for signs to Eyam on the right. As you come into the village, take the first left turn and head past the church to find the car park.

- From the M6, Macclesfield or Buxton – If travelling northbound on the M6 – from junction 17 through Congleton then Macclesfield. Coming southbound on the M6 – junction 19 and follow signs through Knutsford. Both routes – follow signs to Buxton then A6 eastbound towards Bakewell. Approximately 4 miles east of Buxton turn onto the B6049 north-east until it crosses the A623, turn east towards Chesterfield. Approx 2 miles east turn north onto small road to Foolow. Turn east in Foolow towards Eyam.

When it comes to parking, we found that the best place was opposite the Plague Museum. There was a pay and display car park which is the Hawkhill Road one, and it was easy enough to find. The current charges (September 2023) are £1.50 for up to an hour, £2.50 up to 2 hours, £3.80 up to 3 hours, £5.00 up to 4 hours and £6.00 for all day.

Next to the entrance of the Hawkhill Road carpark is another parking spot for the Eyam Parish Council. This is free and you can use it during your visit to Eyam for as long as you choose. At the entrance there is an honesty box where you can donate money to the maintenance of the car park. We chose to park here and added a few pounds to the honesty box, as we felt it would contribute more to the local economy.

Public Transport

Because of how isolated Eyam is, you will find it difficult to get to the village via public transport. There are no trains directly into Eyam, as such you will need to take a bus or grab a taxi. Currently the 65-bus service runs to and from Sheffield and Buxton via Eyam and the 66-bus service runs to and from Chesterfield via Eyam. There are a couple of buses a day between Bakewell and Eyam.

Toilets

Aside from the toilets you will find in the village pub or café, there are free public toilets in a building located on the Hawkhill Road carpark. You’ll see a small circular building at the entrance of the carpark and as you walk around there is an entrance for ladies and gents. We of course had to use them after a long drive into Eyam and found the toilets to be pretty clean, especially considering they’re public and free. There is a donation box by the entrance if you wish to contribute, because the current cost of maintaining the toilets has been taken on by the local villagers.

Dogs

Because the majority of the attractions are around the village, Eyam is the ideal place to take your beloved furry friends. The village even has dog friendly eating spots if you find yourself getting a little peckish from all the walking. The only place which doesn’t allow dogs is the museum itself, unless they are assistance dogs.

Things to do in Eyam Plague Village

We’ve already alluded to it above, but the best part of visiting Eyam plague village is that it doesn’t revolve around one attraction. There are various important historic spots which can be found in different areas of the village. This makes it the ideal all-day activity for those of you who like to walk and ramble in beautiful locations. So let us delve into what you can find there and a little of how it is connected to the 1665 plague.

Eyam Plague Museum

The best place to start is at the Eyam Plague Museum where you can discover more about what the bubonic plague is, its impact on the world and then the story of its arrival to Eyam. They are open six days a week, Tuesday to Sunday, between March and October, and you’ll find them across from the Hawkhill Road carpark. Opening hours are from 10am to 4pm with last entry being 3.15pm and prebooking is not required. The current prices for Summer 2023 are £4.00 for adults, £3.00 for children and £11.00 for a family ticket which includes 2 adults and up to 3 children 5 years and over. You can pay for admission by both card and cash.

The best place to start is at the Eyam Plague Museum where you can discover more about what the bubonic plague is, its impact on the world and then the story of its arrival to Eyam. They are open six days a week, Tuesday to Sunday, between March and October, and you’ll find them across from the Hawkhill Road carpark. Opening hours are from 10am to 4pm with last entry being 3.15pm and prebooking is not required. The current prices for Summer 2023 are £4.00 for adults, £3.00 for children and £11.00 for a family ticket which includes 2 adults and up to 3 children 5 years and over. You can pay for admission by both card and cash.

As you purchase your tickets you will be offered a map of the village which currently costs £1.00 and was incredibly handy as it shows you where all the main attraction spots are and other walks around the village.

Most of the Plague Story is on the bottom floor, but there is an exhibition section up the stairs on the first floor. As you enter the museum you will see the area where you can purchase your tickets and a small shop. Here you’ll find lots of locally made items, as well as toys for the kids (think flea teddy bears), plus books about the history of the plague.

The first room you’ll walk into has multiple boards which display information about what the plague actually is. You’ll discover where the plague came from, what is a plague, its impact on London, the effect of fleas and rats carrying the disease and the various plagues through the centuries.

The next room details how the plague came to Eyam and offers more interaction than the first room. There are models of what the homes of the villagers would have looked like and videos re-enacting the events. Throughout the information provided you’ll discover a lot of details about the families affected by the plague coming to Eyam. This is important because there is a human tragedy which can easily be missed, but the Plague Museum does a great job of bringing the villagers stories to life.

The next room details how the plague came to Eyam and offers more interaction than the first room. There are models of what the homes of the villagers would have looked like and videos re-enacting the events. Throughout the information provided you’ll discover a lot of details about the families affected by the plague coming to Eyam. This is important because there is a human tragedy which can easily be missed, but the Plague Museum does a great job of bringing the villagers stories to life.

Within the third room there’s a continuation of the stories from local villagers and the decisions they made to protect each other and the surrounding communities. This includes population statistics showing the differences before, during and after the plague hit the village.

Before the next room you’ll find a set of stairs, and this will take you to the exhibition room which will change on a regular basis.

Finally in the last room you’ll discover how Eyam recovered from the plague and became a centre for farming, mining, and other manufacturing specialties such as shoes and silk products.

To work through the museum, it takes about 45 to 60 minutes to read all the display panels. If you need to use a wheelchair, then you will find that the ground floor is easily accessible because there is a ramp at the entrance.

In addition to the museum, there are Guided Village Tours available, which when we visited were at 11.30am and 2pm. There is an additional cost to taking part in the tour, and tickets can be purchased at the museum reception.

Plague Cottages

Only a short walk from the museum are the actual cottages where the plague began. The one in the middle is where George Viccars lived who was the tailor’s assistant and the first one to die of the plague. Within that cottage there was a further 3 deaths, two children and their father. The cottage on the left is where all nine members of the Thorpe family died. Then finally the cottage on the right is where the Hawksworth family lived and all, but one died.

Only a short walk from the museum are the actual cottages where the plague began. The one in the middle is where George Viccars lived who was the tailor’s assistant and the first one to die of the plague. Within that cottage there was a further 3 deaths, two children and their father. The cottage on the left is where all nine members of the Thorpe family died. Then finally the cottage on the right is where the Hawksworth family lived and all, but one died.

The beautiful stone cottages are currently someone’s home, as such you cannot go inside them. But there are plaques outside detailing who lived in each and whether they succumbed to the plague. Seeing these quaint little cottages is a startling reminder of how real this story is and how your life can change so quickly.

Eyam Church

Known as St Lawrence’s Church, this Grade II listed parish church dates to the 13th century, although the presence of a Saxon font suggests there was an earlier church on the same site. The church was restored in 1868 and 1870, and the south aisle and porch was rebuilt between 1882 and 1883.

You will find the church and graveyard close to the plague cottages, but you may be surprised to know that only one plague victim is buried there. We spent a little time inside the church taking in the architecture which spans many centuries, but just bear in mind when you visit that this is a working church, so be considerate to the local parishioners. There are information plaques on the walls explaining the history of the church, but make sure you take a look at the stained-glass windows because there is a ‘Plague Window’ which tells the story of Reverend William Mompesson and the plague in Eyam. Thomas Stanley was the original rector for many years but was replaced by Mompesson and both had significant influence over the decision to isolate the village of Eyam.

You will find the church and graveyard close to the plague cottages, but you may be surprised to know that only one plague victim is buried there. We spent a little time inside the church taking in the architecture which spans many centuries, but just bear in mind when you visit that this is a working church, so be considerate to the local parishioners. There are information plaques on the walls explaining the history of the church, but make sure you take a look at the stained-glass windows because there is a ‘Plague Window’ which tells the story of Reverend William Mompesson and the plague in Eyam. Thomas Stanley was the original rector for many years but was replaced by Mompesson and both had significant influence over the decision to isolate the village of Eyam.

Once you’re finished in the church then take a walk around the graveyard. One of the things which will stand out is a Saxon cross in Mercian style which is around 8 feet high. This cross is said to date back to the late 8th or 9th century and originally stood at Cross Low which is west of Eyam. It was thought to be a wayside preaching cross and has beautiful carvings of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and angels.

We mentioned above that one of the victims of the plague village is buried in the churchyard. Close to the Saxon cross is the altar tomb of Catherine Mompesson who was the wife of Reverand Mompesson. After staying with her husband in Eyam, she supported him as he ministered to the plague victims and their families. Sadly, this led to her getting the disease and dying before the plague had run its course. On the last Sunday in August the village celebrates Plague Sunday, and this starts with the laying of a wreath at Catherine Mompesson’s tomb.

Finally on the south wall of the chancel near Catherines tomb is a sundial from 1775. It has the normal inscriptions of hours, days, and months, but also the zodiac, and pointers to diverse locations such as Mecca, Tenerife, and Quebec.

Because St Lawrence’s church is so centrally located in the village, it is an important part of local life. So, make sure you spend a little time wandering around and taking in the breadth of history that surrounds you.

Lydgate Graves

If you’re heading towards the boundary stone, then you will pass the Lydgate Grave site. Although they’re known as Lydgate Graves the names on the stones are George and Mary Darby. Confusing, we know, but the name Lydgate is the street where the grave site can be found.

The graves of father and daughter are found in a walled enclosure and what will surprise you is how close they are to the family home. On one of the gravestones, it reads ‘here lyeth the body of George Darby who died July 4th 1666’. The other grave reads ‘Mary, the daughter of George Darby dyed September 4th, 1666.

Seeing the graves of these two poor souls is a poignant reminder of how much the plague affected the villager’s lives. The fact their bodies are laid to rest just steps from their home and in such a short time from each other, is truly heartbreaking.

Boundary Stone

If you’re willing and able to walk the footpath to the boundary stone, then it’s worth the trek. The views are incredible and it’s an important part of the story of Eyam and the plague. The route to the boundary stone isn’t very well sign posted, so we had to hope that we were going the right way and use the map we bought at the Eyam Museum. At first you walk past a few houses, in fact it feels as though you’re wandering through their gardens. Then there is windy path which seems endless, before coming to a big field. Sat in the middle of the field between Eyam and the village of Stoney Middleton is the stone. You’ll know that you’ve made it because there is a plaque detailing the history and you’re essentially in the middle of nowhere. But being so isolated is the point of the Boundary Stone, which was essential in helping the villagers survive.

If you’re willing and able to walk the footpath to the boundary stone, then it’s worth the trek. The views are incredible and it’s an important part of the story of Eyam and the plague. The route to the boundary stone isn’t very well sign posted, so we had to hope that we were going the right way and use the map we bought at the Eyam Museum. At first you walk past a few houses, in fact it feels as though you’re wandering through their gardens. Then there is windy path which seems endless, before coming to a big field. Sat in the middle of the field between Eyam and the village of Stoney Middleton is the stone. You’ll know that you’ve made it because there is a plaque detailing the history and you’re essentially in the middle of nowhere. But being so isolated is the point of the Boundary Stone, which was essential in helping the villagers survive.

During the plague, the stone was used as a marking point to tell both the villagers of Eyam and anyone from outside that they should not go further. People from the outer villages would go to the stone and leave food or medicine there. The villagers from Eyam in exchange would leave money in one of the six holes on the stone, which at the time were filled with vinegar. They believed that this would kill the infection and make it safe for outsiders to handle. The fact that the villagers of Eyam committed to remaining within the boundary stone at a time of fear, again showed the sacrifices they made.

The Boundary Stone is one of several plague stones marking the boundary to the village and signifying that inhabitants or outsiders should not cross. But this one is quite emblematic to the story of the plague in Eyam.

Cucklet Church

So, we’ll start off by saying that this isn’t an actual church, and we say this because it’s what we expected to see. As we’ve mentioned above, the Reverand Mompesson with the support of the previous minister, introduced a number of safety measures to keep the plague contained. One of them was introducing open air services, and this is where Cucklet Church comes in.

So, we’ll start off by saying that this isn’t an actual church, and we say this because it’s what we expected to see. As we’ve mentioned above, the Reverand Mompesson with the support of the previous minister, introduced a number of safety measures to keep the plague contained. One of them was introducing open air services, and this is where Cucklet Church comes in.

If you follow the signposts for Cucklet Church, you will come to a grassy path and then a large field which slopes down significantly. This can make it difficult for those who are not able bodied, so just consider this before you head over. This area is known as Cucklet Delph (has been spelt as cucklett delf) and it is a limestone crag let which forms a cavern with two large arches.

From 1666 Mompesson used the larger of the two archways as his pulpit and it is here, he would preach to his congregation of concerned villagers: hence it now being known as Cucklet Church. Although gatherings were discouraged during this time to prevent the spread of the plague, it was hoped that being in the open air would reduce the chance of spreading the disease. Family units would group together but stand well away from other households. Just being in that spot you can imagine how important Mompesson’s sermon would have been to his parishioners during such a difficult time. But the beauty of the natural surroundings must have brought them a great comfort.

Riley Graves

Alike the Boundary Stone, Riley Graves are quite a walk from the village centre. They are sadly the spot where eight members of the same family were buried in 1666. Members of the Hancock family are buried in the six gravestones and tomb, enclosed by a stone wall. They are known as Riley Gaves because they lived on Riley Farm and are buried in Riley’s field. Mrs Hancock buried her husband and six children in a mere eight days. She survived the plague and went to live with her son in Sheffield after it was over.

Humphrey Merrill’s Tomb

During the 17th century medical knowledge was limited, so the villagers relied on herbalists. Humphrey Merrill was Eyam’s village herbalist who died during the plague in September 1666. His wife survived and buried him behind their house, with a tombstone marking his grave. On top of the tomb is the initials HM and 1666, but we will admit to not having found it during our visit to Eyam. We walked up and down the streets indicated on the map but had no luck. Hopefully you’ll do a better job than us and find the tomb, if not maybe ask someone who can help.

Mompesson’s Well

Alike the boundary stone, Mompesson’s Well was a safe space for people to leave food and supplies in exchange for payment. During the 1600’s this road was a dirt track off the main road from Sheffield to Buxton and was likely a refreshment stop for horses and cattle. The well is a natural spring and was named after Mompesson after the plague. To walk to the well is quite a challenge, as it is a distance and there is a steep ascent.

Additional Attractions

Although not associated with the plague you can also visit these great spots in Eyam.

Eyam Hall

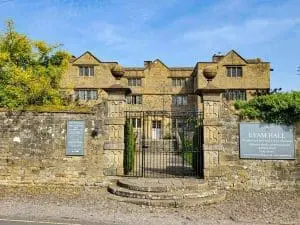

Eyam Hall can be found on the main street and was built in 1671, just six years after the plague. It is a Jacobean-styled manor house and garden which has been the home of the Wright family since 1672. It was leased and managed by the National Trust for five years, until December 2017. You can visit Eyam Hall and learn about the eleven generations of history. Some rooms are closed to the public and the hall could be closed at certain points through the year.

Eyam Hall can be found on the main street and was built in 1671, just six years after the plague. It is a Jacobean-styled manor house and garden which has been the home of the Wright family since 1672. It was leased and managed by the National Trust for five years, until December 2017. You can visit Eyam Hall and learn about the eleven generations of history. Some rooms are closed to the public and the hall could be closed at certain points through the year.

Eyam Courtyard

This can be found in Eyam Hall’s former stable yard and is a great place to explore. Within the yard there are a number of small shops selling locally crafted items, plus there is a café and restaurant so you can rest those feet and grab a bite to eat. Look out for the Eyam Book Barn which is a community shop selling second handbooks and DVD’S.

Eyam Stocks and Information Centre

Across from Eyam Hall is the information centre, where you can find a map of the village and information on what’s available. In front of the centre is a village green and it’s here you will find the stocks which were used to punish locals for minor crimes. They would be held in the stocks by their legs or arms and pelted with stones, clods of earth or dung.

Food and Drink

Because you’ll probably be spending all day wandering around this beautiful village, you’ll work up an appetite. So, we want to make sure we give you a comprehensive list of the food spots in Eyam. They include.

- Café Village Green – Found on the square in the centre of Eyam and ideal for a coffee or cake.

- Eyam Tea Rooms – Again found on the square, they offer home baked cakes, snacks, and all-day breakfast.

- Ivy Cottage – Can be found a short walk from Lydgate and offers a rustic feel. It is a vintage tearoom, so as you would expect there are the usual sandwiches, cakes, and hot drinks, plus so much more.

- The Miners Arms – Offering a great selection of food and drink, the Miners Arms is ideal if you’re looking for a full meal. We stopped in here during our visit to Eyam and loved the local pub atmosphere.

- Stella’s Kitchen – Is an afro Caribbean restaurant which you can find on the way into Eyam.

Accommodation

If you were planning on staying over somewhere during your visit, then why not actually stay in Eyam Plague Village itself. There are a few accommodation options including.

- The Miners Arms

- The Hut Eyam

- Innisfree Cottage

- Eyam Tea Rooms

- Maywalk House

Should I Visit Eyam Plague Village?

This incredible moment in history isn’t known by many people, but the kind of self-sacrifice makes it a place worthy of visiting. The story of the Eyam villagers during the plague is enough to warrant the journey, but then add in the beauty of this little village and you’ll see why we fell in love.

This incredible moment in history isn’t known by many people, but the kind of self-sacrifice makes it a place worthy of visiting. The story of the Eyam villagers during the plague is enough to warrant the journey, but then add in the beauty of this little village and you’ll see why we fell in love.

The best part is, that although there is a cost to visiting Eyam Museum, everything else is completely free. This makes it a pretty low-cost day out, especially when you compare it to the local attractions to Eyam such as Chatsworth House.

If you’re wanting to see everything on the map then there is quite a bit of walking, well, we should say rambling because the outer attractions can be difficult to get to. Parts of the walk are steep and rough underfoot, so make sure you have appropriate footwear and clothing. But that adds to the fun of the day, and you have the opportunity to take in some incredible views and naturally idyllic spots.

To help manoeuvre around the village we would recommend getting a map from the museum, even though there is a cost. You will find lots of information boards around with one being in the car park and another the village green, so you could always take a picture of the map on your phone.

There are lots of signposts directing you to the main things to see, although we did find that they disappeared for the attractions which were a distance, such as the Boundary Stone. This again is why it’s handy to have a map, so you can gauge where abouts you are heading.

It’s worth noting that Eyam is a residential village and as such you’re walking around people’s homes. This includes the Plague Cottages, where there are plaques commemorating the victims of the plague, but the buildings are lived in. They welcome tourists but you should walk on pavements and not the roads and respect the ‘no parking’ signs when displayed.

The fact that so many of the original homes and relics from the plague remain in the village gives it a mythical feel. Add in the incredible setting in the Peak District and you’ll find that visiting Eyam will be memorable, and it’s just a short drive to the Heights of Abraham; just remember to take plenty of pictures.

If you do visit Eyam Plague Village, then please tag us on your pictures on Instagram, we love to see what our readers are up to.

Eyam is the ideal place to go to in the summer, so why not add it to your Summer Bucket List.